If I had to locate a meeting point between psychology an linguistics, it would mostly likely be in the principle of linguistic relativity. What is known as linguistic relativity, or the “Whorfian/-Sapir hypothesis”, is a principle developed by linguist Benjamin Lee Whorf and his mentor Edward Sapir which essentially held that language effects the way speakers perceive, conceptualize or build their worldview, which would otherwise effect thought processes(Swoyer, 2010); different languages would represent different ways of thinking. Much of what has been assumed by the academic majority, in psychology or linguistics, is the notion that language bares no relationship to how we think, much less how and what we perceive. The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis states that language to some degree affects our cognition in regards to the context and area you live in. Although not much research has been dedicated much the relationship of language, thought, and perception, there has been a few preliminary studies done to suggest that there is a relationship. Well, at least enough to garner some worthwhile curiosity.

In addition to the idea of different languages causing perceptual and thought-based differences, I think the notion of the Whorfian-Sapir hypothesis lends credence to the idea that language in some senses determines what we see in the world. For instance, there have been many studies performed on various cultures in language, the perception of color, and the varying degrees of perceivability of color as a result of structures in language(Özgen, 2004). There is also the fact that language, or in this case linguistic labels, effect the way we perceive more complex targets (Eberhardt, et al., 2003); examples of those labels being “white”, “tall”, “fat”, “slow” etc. Such inquiries not only suggest that perception and language have a relationship but it also suggests, to an extent, as mentioned earlier, that language plays a determining factor in what is being seen from our perspective. And just what we see will in some way be influenced by context (i.e. culture and geographic location with its languages and customs in those languages).

Learning, Perception of Color and Geographic Location

One of the principle aspects to our vision is color. It is incorporated into our daily lives; we use color to distinguish whether we should stop or go at a traffic intersection, we use color when we are in a parking lot looking for our vehicle, we even use color to help us navigate on a GPS or map. With all the examples we can think of, we recognize the need for color distinction as taken for granted since it has become such a fundamental and often used tool of reference in our lives. Even those afflicted with color-blindness use perceptual differences in “color”, that is, they use the differences in hue regarding black and white colors; differences in lightness and darkness.

Nevertheless, Emre Özgen PhD conducted a study in 2004 that would look into language, color, learning, perception, and the differences in them regarding your geographic location. The study took into consideration that African languages have up to five primary words for colors but that Russian languages have as many as in the English language, with an additional shade of blue (Benson, 2002). Though there have been many studies before that shed light on perceptual differences in color, Özgen wanted to find out some more intriguing questions: Can training enhance the effect, making people more sensitive to color differences across geographic boundaries? Can perception be improved through instruction and training in a lab?

In the first objective, experiments involved the answering the question whether training can improve the subject’s ability to distinguish between differences in primary color; that is, differences in hue. What the experimenters were looking for here is whether participants can distinguish between colors like bluish-green, yellowish-green, redish-green and so on.

The second objective of the study involved a second question: whether those novelties in categorization of color can be reproduced in the lab.

The subjects were trained to divide primary colors, blue and green, into two new categories. The boundaries of the new categories lay at the focal points of the old categories–the greenest greens, for example, now lay at the boundary between a category of yellowish greens and a category of bluish greens (Benson, 2002). Then, after three days of training, the subjects were able to distinguish between both categories within primary color schemes. Even when the distinction was minor. The “natural” boundaries between color were overridden by the research experiment. Such training revealed that subjects, with even the lowest amount of color distinction, can learn to spot differences in hue when before training were not able to perceive such differences by sight alone(Özgen, 2004).

When you take into account that geographic regions along with their language constructs effect the mundane awareness of color, you begin to see the importance of language and its effects on what colors you see, or even in general. Expanded notions of color can go a long way.

Culture, Ethnicity, and Linguistic Labels

To think that the culture you grew up in has an effect on your perception is inconceivable to most laymen. So any thought of it would not surface to anyone with a cursory standpoint on the matter. Cultural-normative labels, or stereotypes, we have for certain ethnic groups would carry with it universal characteristics we non-consciously apply to those labels. This interested Jennifer Eberhardt, a social psychologist at Stanford University, and so she decided to further look into the possibility that these labels we apply to particular ethnic groups revealed something about our perception.

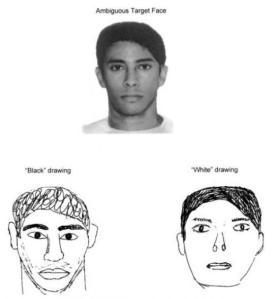

Eberhardt and her colleagues (2003) decided to show a picture of a man who was racially ambiguous to white college students. He could have plausibly fallen into the “white” or “black” category. One half of the white group the face was described as that belonging to a black man and the other half the face was described as belonging to that of a white man. The experimenter then asked the students to spend four minutes sketching the picture as it lay on a screen in front of them.

Even though all subjects were looking at the same picture in front of them, the subjects that were hung-up on the idea that physical characteristics belonged to a certain ethnic group (see figure below) matched the stereotypes that belonged to those ethnic groups. What the experiment showed was that the subjects who attributed stereotypical characteristics belonging to ethnic groups, saw the picture, the racially ambiguous man, through those stereotypical filters–they were incapable of perceiving the man independently from the ethnic stereotype in regards to the labels of “white” and “black”.

What was important about this study is that it revealed how far labels(i.e. ethnic stereotypes) effect us; down to our perception, what we see. What is more intriguing is the fact that we can attribute physical characteristics to that label and as a result of repeated use and cultural conditioning, we can begin, or at least some of us, to witness the effects of those labels being felt in what we perceive. Further evidencing the fact that language constructs and its customary use, to a considerable degree, prevents us from perceiving the actual qualities of an object, or as the phenomenologists hold; the object-in-itself.

Conclusion

The important thing to grasp from these studies, is that language, along with its customary use, does indeed effect perception to some degree. It can in some instances prevent us from perceiving the authenticity of an object. Whether it be something a basic as color or something as impactful to our ethnic relations as the physical characteristics we non-consciously attribute to one another, one thing is suggested here: the real world is a description of our language and not language as a description of the real world. Now to say that language creates what we see? and is in a sense constricted by it? That is something for future researchers and investigators to confirm or deny. But in any case, one can see the effect that stereotypical labels and the degree of descriptiveness in language constructs have on something as important as perception.

References:

Benson, E. Different shades of perception. Monitor on Psychology. Vol 33, No. 11. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/monitor/dec02/perception.aspx

Eberhardt, L., J, & Dasgupta, N, & Banaszynski, L., T. Believing Is Seeing: The Effects of Racial Labels and Implicit Beliefs on Face Perception. Sage Journals. Vol. 29, No. 3 360-370. Retrieved from http://psp.sagepub.com/content/29/3/360.abstract

Özgen, E. (2004). Language, Learning, and Color Perception. Sage Publications Inc on behalf of Association for Psychological Science. Vol. 13, No. 3. pp. 95-98. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20182921

Swoyer, C.(2010). Relativism, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edward N. Zalta (ed.). Retrieved from http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/relativism/supplement2.html

Pingback: Language Creates Consciousness: Behaviorism and the Origin of Consciousness (A short account) | Reflections·

Pingback: URL·

Pingback: Psychological Hurdles in Psi Research: Beliefs and Expectations Effect Research in ESP? | Reflections·